STRANGERS IN THEIR HOMELAND by Akli Bessadeh, Libya

I was born in a very small village in the Acacus Mountains of Southern Libya to a nomadic family with two brothers Awaden and Mawli and two sisters Djanit and Aicha. My father is a typical Tuareg man whose dignity and honor are praised by the people who know him. He is very proud of his culture and is well respected by others, as is my mother Tinhinan. My father is very tall, like most Tuareg men and has a long mustache. He’s not a very talkative person and in accordance with our culture we hardly talk to him about anything, not even about his experiences or journeys. These would sometimes take a couple of weeks or even two months without us seeing him at all. I remember him once saying to me, while he was busy putting a saddle on his camel: ”You know my son, when I sit on this saddle I feel as if I’m sitting on the top of the world’’. When he’d finished saddling the animal he would ride away into the distance until he finally disappeared over the horizon. He would not show up again until his journey ended three weeks later. My mother was also a tall person and had long hair tied in a ponytail. She talked a great deal, about all types of subjects. In this way, she was the opposite of our father.

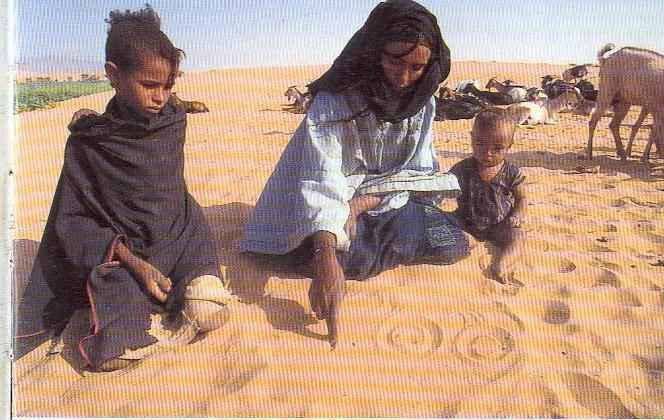

According to our culture, the first thing you have to learn in life as a child is how to read and write using the ‘Tifinagh’ script. Mothers are the ones who take on this role; every mother in Tuareg society is a teacher. Along with two of my eldest brothers I had to sit around the fire, for hour after hour, repeating the words while writing them on the sand, until, eventually, we’d all fall fast asleep.

In the 1970s and ’80s drought struck most parts of the Sahara Desert, and many Tuareg nomads, including our family, lost their animals and livestock. New refugee settlements had to be built on the edge of various growing towns and cities in the south of Algeria and Libya. In 1980, three years before I was born, Colonel Qaddafi invited the Tuareg to what he calls himself the original homeland of all Tuareg (Libya). In 1980, three years before I was born, Colonel Qaddafi made a number of promises to the Tuareg in Libya, including good housing and free education. He even promised Libyan nationality. His invitation even reached as far as Timbuktu. Hundreds of nomads from all parts of the Sahara made their way to Libya. Qaddafi’s people received them in places that looked like refugee camps but with promises that they would provide better accommodation for them and their families. Later however it became clear that Qaddafi’s historic speech was merely political rhetoric and not of any help to the Tuareg, as many had expected at the beginning. In fact Qaddafi’s purpose was to recruit more soldiers for his weak army, to fight his wars in Chad, Lebanon and elsewhere. Qaddafi knew how good and fierce Tuareg fighters were. But many Tuareg nomads who answered Qaddafi’s appeal simply ended up living permanently in refugee camps and ghettos without any citizen’s rights. Against their wishes their children were sent off to fight Qaddafi’s hopeless wars, eventually lost, in Chad and Lebanon. Many of them were either killed or ‘disappeared.’

I was only six years old when we moved into ‘Alttyouri Camp,’ in Sebha, 700 km south of Tripoli. I call this horrible place a ghetto. It was one of many camps that the Qaddafi regime established as an open prison in which to gather his victims before sending them off to the front lines in Chad and Lebanon. It was one of the worst and dirtiest places on the planet. There was only a single drinking-well where people could get drinkable water. All the houses were made of mud and there was no sewage system. The streets were extremely narrow, and the whole neighbourhood was surrounded by a huge wall. This was in order to prevent the people inside from being connected to the outside world. It was also built to hide the appalling and inhuman conditions in which the Tuareg were living.

‘Alttyouri Camp’ and the people forced to live there are the same today as 30 years ago. Despite the Libyan Revolution, the Tuareg there continue to live totally ignored by all the consecutive governments that have followed the fall of Qadaffi. Many children are unable to go to school to study because they lack full Libyan nationality and thus a national number as well.

The longer I live the more bewildered I am by a whole lot of questions that insistently present themselves. Just one example is this: “What on earth makes successive governments treat us like dirt, as if we were complete strangers although living all the time in the land of our birth?”

Leave a Comment

Want to join the discussion? Feel free to contribute!