Queer Stories Hidden in the Cracks of the Land

Quick, answer these questions! What year was the first pride parade in Tel Aviv? Off the top of your head, who is one impactful Israeli LGBTQ+ activist? Your answers to these questions would probably be ‘I don’t know’ – which exactly shows the problem. LGBTQ+ rights are frequently discussed in Israel and Palestine – but the foundational history of these discussions is rarely mentioned. The history of the Israeli LGBTQ+ community is invisible to the public – and it is a struggle to find the resources for it even when you’re looking. But it is still a topic with many questions that demand answers. In this article, you will learn the history I uncovered – and the many reasons it remains covered.

LGBTQ+ history is not a subject left unexplored in other countries. The German LGBTQ+ community proudly presents its history in a public museum. In the USA, there are multiple organizations; the GLBT Historical Society, the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, and the Stonewall National Monument. Israel, however, does not value its LGBTQ+ history in the same way other countries have and is therefore lacking in the respect and roots other LGBTQ+ communities thrive on. History provides us with respect for the accomplishments before us, a clear view of what needs to be done in the future, and a base for our identity. This is all the more needed with the LGBTQ+ community, since our heritage isn’t passed down by our families.

Raphael Eppler Hattab, an LGBTQ+ activist from the 80s and the first openly gay Israeli reporter, elaborates on the importance of history: “…it helps to get an understanding about the size of the change and the depth of the change that happened here… It gives… a worthy space of respect for the community’s older members, to come and tell their stories… heterosexual families pass on their legacy to their children and grandchildren, and we [the queer community] have that less. …There is a real need here for older homosexuals and lesbians to pass on their legacy to the next generation.”

Let’s take it back to the beginning; Judaism forbids homosexuality in the third book of Moses. The Quran, too, condemned homosexuality as a sin. The first change was in 1858, when Palestine was under Ottoman rule, and the laws criminalizing sodomy were abolished. By 1920, however, under the British mandate, homosexuality was prohibited again. The only history we know of then is that British soldiers themselves had ties to the origins of cruising spots (cruising spots are places in which gay men publicly looked for sexual partners) in Israel; in the 1930s, the spaces near their camps were popular spots.

Most of our knowledge comes from legal cases of sex between Jewish men, Arab men, and British soldiers but those rarely showed cases of romance or relationships. Through personal accounts and journalistic articles of the time, we also know there were cruising sites along Tel Aviv’s beaches (this place was often called the Strich – meaning “the stretch” in German – by immigrant gay Jewish-German men), cafes and clubs in which gay men gathered and socialized. There is little documentation of lesbians at the time, but eyewitnesses reported that these relationships existed, and it was clear that these women were in love, but it was never spoken of.

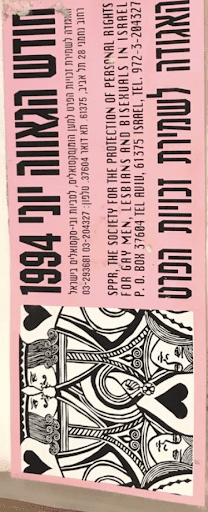

The history of the LGBTQ+ community after 1948 is scarce – most queer activity in this era happened in Binyamin Garden in Haifa and Azhmaout Garden in Tel Aviv as a cruising spot for gay men, a place for the community that was often diverse, people of all backgrounds and ethnicities gathering there. However, in 1963, sodomy laws were no longer enforced. After that, the story continues with most of the queer community finding each other through whispers and gatherings in the garden, followed by private invitations to home parties. In 1975, the first public queer organization was founded, the Aguda, the organization for queer rights in Israel. In 1977, they organized the first pride event in Israel in Hayarkon Park. In 1983, the first lesbian organization, “Isha Leisha” (women to women) was established. Queer people managed to find each other – but the heteronormative majority of society wasn’t aware of the idea of homosexuality until the AIDs crisis. Raphael Eppler Hattab, for example, learned about his identity through reports of AIDs.

The history of the LGBTQ+ community after 1948 is scarce – most queer activity in this era happened in Binyamin Garden in Haifa and Azhmaout Garden in Tel Aviv as a cruising spot for gay men, a place for the community that was often diverse, people of all backgrounds and ethnicities gathering there. However, in 1963, sodomy laws were no longer enforced. After that, the story continues with most of the queer community finding each other through whispers and gatherings in the garden, followed by private invitations to home parties. In 1975, the first public queer organization was founded, the Aguda, the organization for queer rights in Israel. In 1977, they organized the first pride event in Israel in Hayarkon Park. In 1983, the first lesbian organization, “Isha Leisha” (women to women) was established. Queer people managed to find each other – but the heteronormative majority of society wasn’t aware of the idea of homosexuality until the AIDs crisis. Raphael Eppler Hattab, for example, learned about his identity through reports of AIDs.

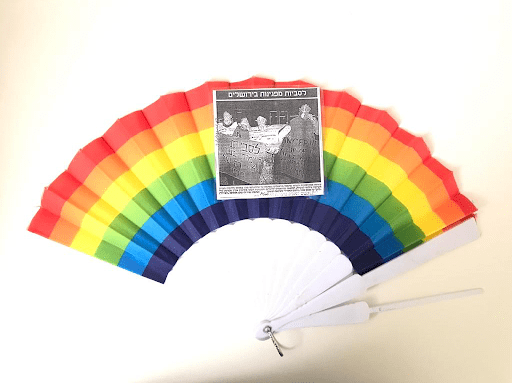

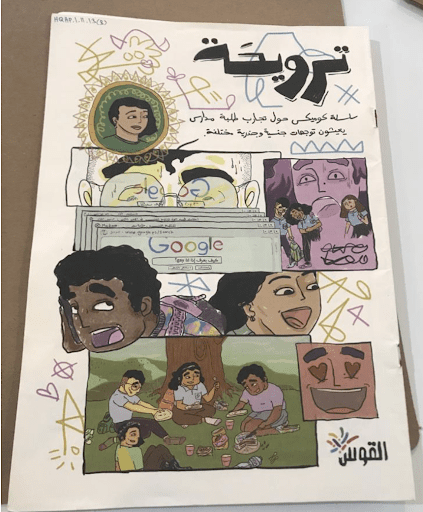

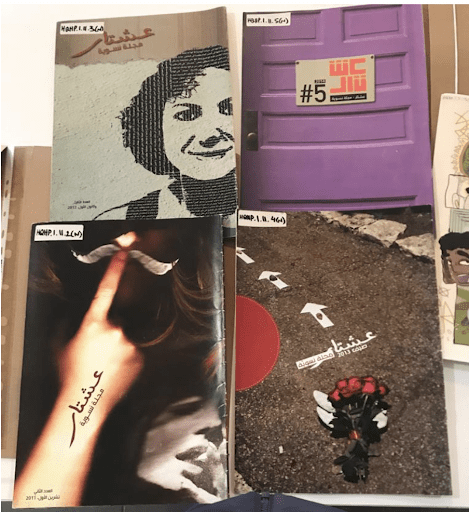

By 1988 the law against homosexual sex was officially eliminated, and in June of 1989, the country celebrated pride week for the first time. Since then, pro-LGBTQ+ laws have passed more and more – in 1992, anti discrimination laws in the workplace passed, in 1993 LGBTQ+ people were allowed in the military, and that same year, the first LGBTQ+ conference in the Knesset was held. Pride parades began surfacing in many cities, and queer journalism began thriving. Even though most of the celebrities we now know as queer were still closeted, the community’s visibility was starting to evolve, and it wasn’t necessary to rely on knowing the right people to find yourself. The Palestinian community also had its accomplishments; even though homosexuality is still illegal in the West Bank, Aswat, an organization for Palestinian lesbians, was founded in 2003, and alQaws, an LGBTQ+ rights group for Palestinians, was founded in 2007.

By 1988 the law against homosexual sex was officially eliminated, and in June of 1989, the country celebrated pride week for the first time. Since then, pro-LGBTQ+ laws have passed more and more – in 1992, anti discrimination laws in the workplace passed, in 1993 LGBTQ+ people were allowed in the military, and that same year, the first LGBTQ+ conference in the Knesset was held. Pride parades began surfacing in many cities, and queer journalism began thriving. Even though most of the celebrities we now know as queer were still closeted, the community’s visibility was starting to evolve, and it wasn’t necessary to rely on knowing the right people to find yourself. The Palestinian community also had its accomplishments; even though homosexuality is still illegal in the West Bank, Aswat, an organization for Palestinian lesbians, was founded in 2003, and alQaws, an LGBTQ+ rights group for Palestinians, was founded in 2007.

While I did manage to uncover a fair amount of LGBTQ+ Israeli history, many things remain unexplored and unknown. The problem is how difficult it is to uncover this history – before 1948, the only people to bear witness to queer life were eyewitnesses or newspapers and legal cases which depicted homosexuality as a crime. After 1948, it is still difficult to find records since so little LGBTQ+ life was made public or documented. The queer gatherings spread from word to mouth. Books with queer characters were dismissed as smut. Even after homosexuality was legalized, many people were still closeted and participated in queer life through secret mailboxes. We can see how censorship in society affects historical narratives by looking at the community of which we know the least about; queer Arabs. Queer men who speak out about queer rights in the West Bank are often arrested and abused, as those who managed to escape can tell us. In conclusion, queer life was separate from the majority of heteronormative society and thus undocumented.

Of course, there are Israeli LGBTQ+ history projects; The Haifa LGBTQ+ history project is an extensive archive, and the Aguda has its own Israeli-wide history project. While some of these projects have made it to academic circles, they are still a topic you rarely see in universities’ libraries. In the past, historians were simply disinterested in this aspect of Israeli society, either because the current methods of documenting are considered less professional and reliable (oral history) or because they simply did not think of it. This has changed in recent years with the above mentioned projects, but decades without historical interest have left their impact. Raphael Eppler Hattab, who in recent years has become a helpful assistant to LGBTQ+ history projects, says this: “…until recent years, there was no documentation… if I look at historians… I think there was no awareness, and there were no studies about the need to research the history of the LGBTQ+ communities in Israel.”

When interviewing my two witnesses to LGBTQ+ history, it is no surprise that the topic of the new government came up when I asked them about the future struggles of the LGBTQ+ community. Hannah Safran, a lesbian activist since the 80s and an academic of LGBTQ+ history, said: “…the rights of the lesbian, queer, and LGBTQ+ community… are in danger… There is still a community here with a sense of accomplishment, and I hope this success doesn’t fail… nothing is promised. …at this moment, we can only hope, go out and fight and work together with other people.” With the current government threatening our right to exist all over again, it is essential to know our history and learn from it in order to preserve our current rights.

Dotan Brom, one of the founders of the LGBTQ+ Haifa History project, explained why history is important for future generations: “…in Haifa, hopefully, there is a young generation growing that knows they’re a link in a chain… that feels a responsibility for the queer LGBTQ+ community in the city because they know that Haifa is its home too and that their story is inseparable from [Haifa]’s story.” LGBTQ+ history is important to research, especially in Israel, because our fight is not over yet; homophobia isn’t eradicated, and we do not have the same rights as heterosexuals do- but we need to know about our past and what we gained in order to be hopeful for progress and keep fighting for a better home, right here.

After learning about all of this fascinating history, I have found and discovered why LGBTQ+ history is important and should be studied more in every country. Especially here, where the fight has a long way to go – I urge you to find out by yourself about Palestinian, Jewish, and Israeli LGBTQ+ history to help bring to light this aspect of our history and find out what I couldn’t have – if it is through uncovering the stories of LGBTQ+ elders or researching in old archives. This will further our struggle for rights in the future and help us learn how not to make the same mistakes.

Leave a Comment

Want to join the discussion? Feel free to contribute!